Advertisements in newspapers are terrains worth exploring for their historicity. These sources serve as time capsules to a society’s material concerns and needs at a specific context. While some advertising strategies change over the years, marketing the needs and concerns remains constant and reveals how the present intimates its connections with the past.

Source: Microfilm Collection of the Rizal Library, Ateneo de Manila University.

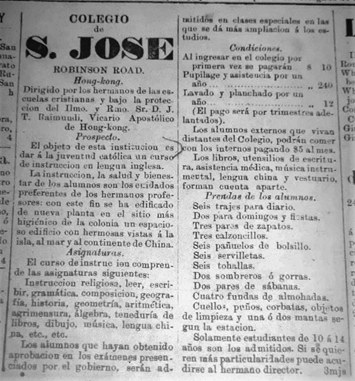

This advertisement for a school in 1887 caught my attention on my last trip to Manila. It did not have any elaborate images nor was it printed in colour (typical of advertisements and news printing of the period). But when I saw the words “Robinson Road” and “Hong Kong”, as a PhD student studying in HKU, this piece naturally took me away from what I was intending to find.

The advertisement is about a school named “Colegio de San Jose” found along Robinson Road in Hong Kong. Written in Spanish, it promotes an institution that “provides the Catholic youth education with English as the medium of instruction.” It claims that the school’s teachings and students’ health and welfare are well-taken care by professors who were also religious brothers. This is accomplished by having the school built on “the most hygienic site in the colony, with a spacious building and elegant views of the island, sea, and the Chinese continent.”

It is particularly curious to include the “hygienic” aspect as a school’s selling point. In the nineteenth century, Hong Kong was considered as a swampland of diseases. Smallpox, malaria, beriberi, acute dysentery, and cholera were among the top causes of mortality throughout the colony. By the latter part of the century and well into the next, the island bore the brunt of the bubonic plague. While most of its diseases were exacerbated by poor personal and environmental hygiene, a great majority stemmed from the continuous connections built by Hong Kong as an emerging entrepot. The influx of Chinese traders and speculators, ships from Singapore, Philippines, and Batavia, British colonial officers, and foreign settlers contributed to the city’s urbanization. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Hong Kong had swollen into a major, but highly vulnerable, colonial port.

If Hong Kong was riddled with problems of disease and sanitation, in what way was it an attractive place for education? As a British colony, official transactions were conducted in English, a language that was closely associated with commerce and progress. During the period, the British empire overshadowed the Spanish empire in terms of naval strength, the expanse of territory, mercantile and industrial power, and technological advancement. Along with the Straits Settlement (now Singapore), India, and British Malaya, the grasp of the British Empire in the Far East was felt through the commercial linkages it made.

Hence, learning the English language became a fundamental requirement to participate in global progress. In the Philippines, this was understood mostly by landowning creole (mestizo) families. Many of the landowners produced crops for export such as sugar, hemp, and tobacco which required substantial access to English-speaking markets in the region. Banks from Hong Kong expanded its operations to the Philippines: the Standard Chartered Bank in 1872 and the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation in 1875. However, after a close control and suppression of subversives in the 1870s, a considerable number of these families had opted for their children to study outside of the Philippines.

In an indirect manner, the Colegio de San Jose responded to this opportunity. As an institute of education, the college promised to provide a comprehensive education for prospective students in the English language. In addition to the study of practical (reading, writing, grammar, composition) and liberal arts (geography, history, geometry, mathematics, agronomy, algebra, accounting, drawing, music, and Chinese), the school provided a Catholic education, a feature that appealed majority of Philippine families.

But as an establishment, the advertisement was clear that the school was not meant for all. It included costs of education from entry, tuition, dormitory, food, and laundry which could only be afforded by a few families. Moreover, apart from the books, medical insurance, musical instruments, and other supplies, students needed to procure for themselves a wardrobe befitting of a proper student: “six everyday suits, two Sunday and feast suits, three pairs of shoes, three pairs of underwear, six handkerchiefs, six napkins, six towels, two hats or caps, two pairs of bed sheets, four pillowcases, neckties, cuffs, shirts, and blankets.” Talk about a full wardrobe.

In many ways, this advertisement is not detached from the experience of international students of the twenty-first century. An international education often appears as glamourous and advantageous, participating in becoming a global citizen. It provides the promise to be included in a world of opportunities. Whether for personal career or other motivation, and international education introduces students to look beyond the local and appreciate how much of the borders that appear are human constructs.

Yet, beneath the veneer of the international allure lies the truth about local inequalities in global learning and education. For many of us, we have witnessed the inadequacies of education in our home countries. Back in my home country, we are still plagued with a lack of facilities, textbooks, and proper pay for teachers while the government chooses to invest in erstwhile activities like the drug war and citizen surveillance. Lack of investment, laboratory facilities, research grants, and expertise persuade most of us to seek better educational opportunities. With many having the same type of degree, seeking employment opportunities become equally tough in an already competitive job and academic market. Hence, to use advertising parlance, an international diploma becomes our unique selling point.

Unfortunately, as much as we want, international education is a commodity that cannot be attained and enjoyed by all. Not all families have the means to send their children to top-notch institutions, more so have access to proper education. Structural inequalities as by-products of colonialism and neoliberal market policies provide degrees of privilege for some, and to an extent, at the expense of others.

To recognize that some have varying levels of privilege allows us to realize that what some enjoy can only be dreamed of by many. These are translated as products and services, and we are reminded every day about the problem of privilege. Take the advertisement of the Colegio de San Jose for instance. It was placed in El Comercio, a Spanish periodical for commercial and mercantile traders in Manila. It spoke directly to the parents of Spanish and mestizo families, who made a very small fraction of the Philippine society. Privilege has an intended audience too.

Today, we see these patterns regularly without realizing it. When we walk inside the MTR, we are immediately greeted with a host of advertisements about what one should look, wear, or feel like even. We recognize these when we browse through shopping catalogues on the internet, and impulsively buy things on credit. But the moment that we look into these advertisements and interrogate them is to check one’s privilege—to recognize the inequalities that pervade us on a daily basis.

Photo courtesy of Gwulo Old Hong Kong (https://gwulo.com/atom/28966)

The Colegio de San Jose still exists today as St. Joseph’s College. According to its website, the school transferred its campus from Robinson Road to its modern-day location in Kennedy Town. Now celebrating over 140 years, it continues to offer a Christian secondary education under the Lasallian Brothers. It is providential to think how these ties from the past are intimately linked to the present while I sit atop of Lung Wah Street, having the privilege to think about home.