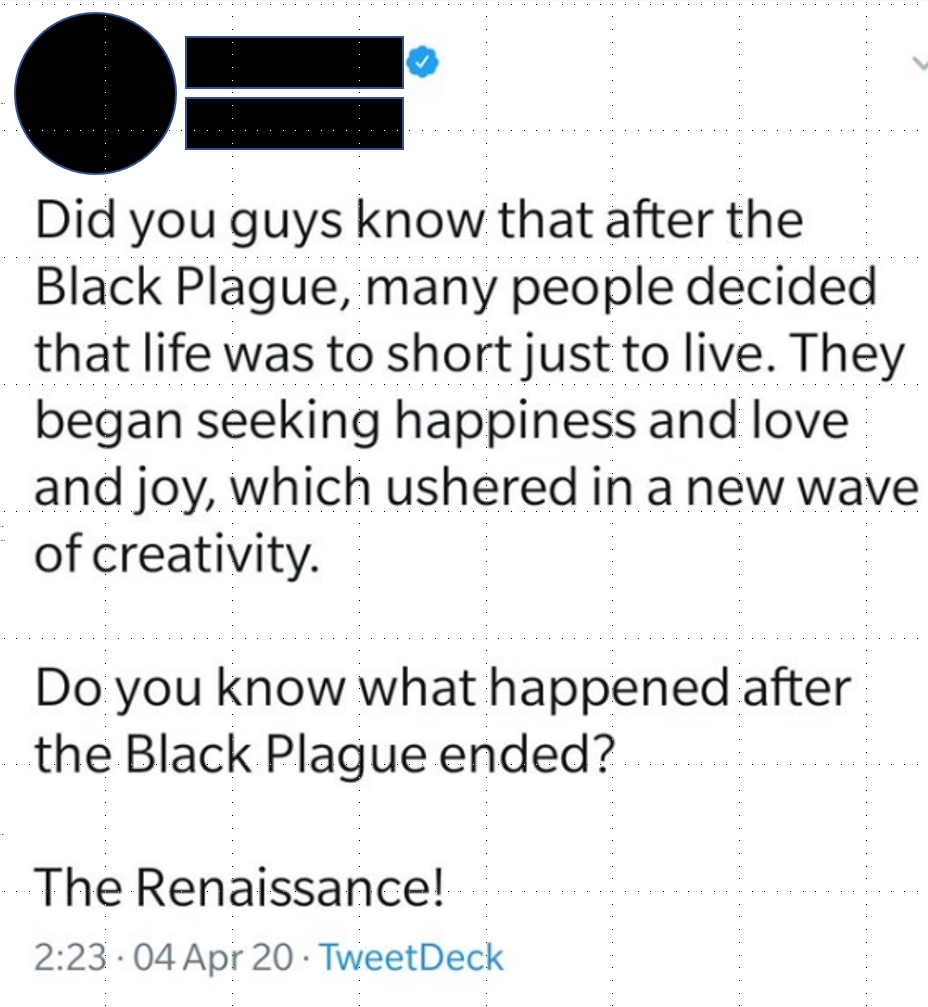

Consider this post that was made viral on Twitter on 04 April 2020:

In this tweet, the post’s author was trying to make a comparison with the Black Plague/Black Death with the coronavirus CoVID-19. The epidemic that caused the mortality of millions of Europeans in the fourteenth century is being linked to the rise of the Renaissance. A period of great works of art, the revival of Roman ideas and values, and time of grand architecture, the era had been considered as the “break” from the bleak and dark Medieval Ages.

To the ordinary reader, this makes sense. In middle or secondary school, students are taught that what follows the Black Plague was Renaissance. Pedagogical instruction in history was for the most part all about chronology, or the proper sequencing of events. This may have led many people to conclude that moments of decline would eventually lead to periods of growth, as seen in the sequencing of the two periods.

However, this reasoning is a very dangerous proposition as it considers two things: first, that the promise of “normalcy” is guaranteed. Furthermore, it proposes that the end of every crisis or pandemic there would be an great period of prosperity and growth (and in the case of Renaissance, a time of cultural development).

This tweet also comes at the time when criticism about philosophers who speak up about the pandemic. In a rather controversial post, one historian asserted that philosophical inquiry, as urgent as this epidemic, “can turn out shoddy and defective.” Invoking Ludwig Wittgenstein’s the philosopher’s silence as apropos, he advises, “Perhaps those previous generations of less entitled, less celebrated, philosophers were prudent to sit out their epidemics, and to reflect in tranquillity.”

In many ways, this comment also extends to historians and other academics: the battlefield for which the historians ought to be concerned with is the past. Yet, in a highly controverted and rather extraordinary situation like the pandemic that we experience in our own lifetime, the call for silence, more specifically, of “sitting out” is counterintuitive, if not a form of injustice. Unfamiliarity and uncertainty provide us the natural inclination to refer to the past for wisdom. Despite the many pandemics that have occurred in the past, this particular pandemic has characteristics that we are yet to comprehend. Consulting history in search for answers not only renders the “usability of the past”, but it keeps us abreast about the universalities and particularities of this discipline.

This propensity to look into the past for answers is precisely the due cause for historians to not remain silent, especially in a crisis. Indeed, pandemics are better resolved through the use of medical-scientific knowledge: epidemiological models, transmission rates, and the like. But the experience, approach, and reaction throughout societies are varied. As we have all experienced through lockdowns and quarantines, epidemics and pandemics cut across various geographic, economic, social, and even cultural realities. It is in the latter that historians can also take part, shed light to these complexities, and to an extent, render advise.

Historians survey and see the entanglements of the past by studying various histories. With the past as having “a country of its own,” this terra incognito expands and overlaps with both past and present. Historians charter this terrain by meticulously investigating and understanding documents and artefacts. Hence, one of the main tasks of a historian is to aid general readers make sense of the past by placing a prime on accuracy.

This is seen in responses that make the apparent “link” between Black Death and the Renaissance. In a separate post, a medieval historian has called out the historical inaccuracies of this presumption, and warned about connecting these episodes:

The exhortation to take heart from the idea that the Renaissance followed the Black Death is yet more dubious. As I always tell my students, the Renaissance was something that happened to rich people. The fact that a few outrageously wealthy individuals in Florence could buy a nice painting had absolutely nothing to do with the lives of the masses. The agricultural labourers making a few more coins a day would never see a Leonardo da Vinci sketch, much less a finished work.

Eleanor Janega, “Don’t kid yourself. The Black Death’s aftermath isn’t cause for optimism about Covid-19.” The Washington Post. 14 April 2020.

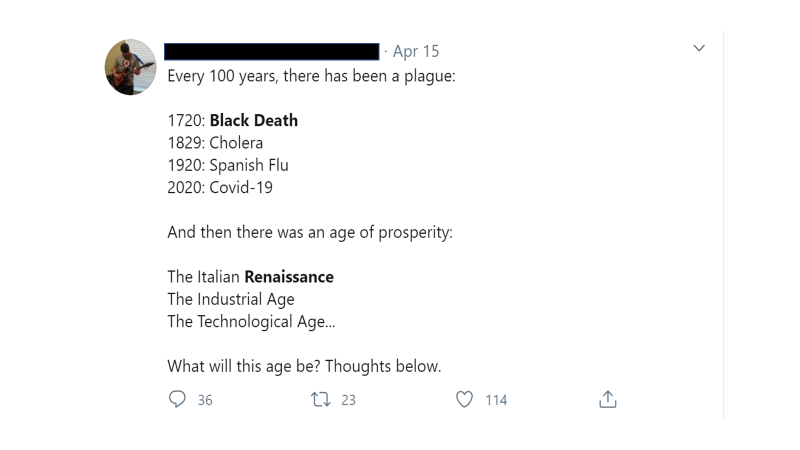

This level of untangling and explaining is much needed. It challenges the common thought that history consists of a neatly-ordered series of events. Or worse, patterned. Consider the next tweets:

The first tweet is premised that epidemics and pandemics had ushered “ages of prosperity”. Since the Black Death (not in 1720), cholera, and the Spanish flu came before the Italian Renaissance, Industrial Age, and Technological Age respectively, then it would not be a surprise if something great emerged after the current pandemic.

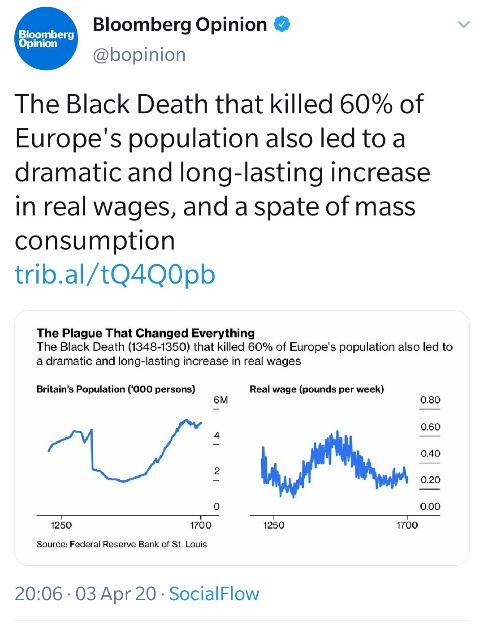

The second tweet tackles the “positive” side of having the pandemic. After the Black Death, many states in Europe had taken advantage of the lower interest rates to create businesses and mercantile companies that fuelled the economies of fifteenth-century mercantilism. Moreover, the author suggests in the linked article that “by laying bare the fault lines of production that rely on people to come together on buses, trains, planes and in offices and factories, the virus could hasten the age of the robot and the algorithm. Since automatons need no pay, the demand deficiency could worsen.”

Both of these tweets suggest that moments of crises in the past are beneficial, if not necessary, to those who are living in succeeding generations or of those in the present. Of course, historians are concerned with commemorating past events. But these periods of crises involved real people who once lived at a specific moment in time and space. To write off the actual suffering of real people, many of whom did not choose to die prematurely, devalues their lives. And while we yearn to make sense of the past, history should not be used at the expense of reducing their memory as mere casualties or gains of the present.

In this sense, historians serve not only to interpret the past but act as to ensure that such injustices are not forgotten. This cannot be accomplished by sitting out on what is happening in the present. Whether during peacetime or crisis, historians are obliged to speak up. As the political philosopher Hannah Arendt puts it, “Action, as distinguished from fabrication, is never possible in isolation; to be isolated is to be deprived of the capacity to act.”