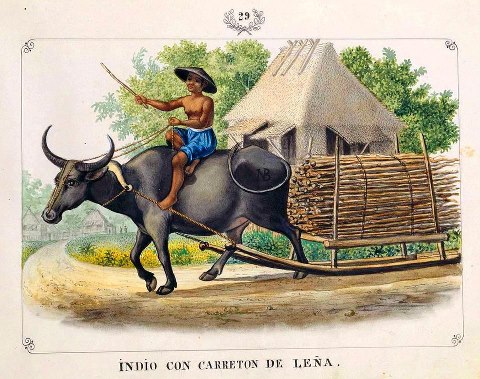

In the past two years that I have been writing my master’s thesis, I can already consider myself as an expert of the Philippine carabao or the water buffalo. The perennial “beast of burden” is a highly endeared animal to Filipinos especially for those whose economic survival depended on. In my study, I have explored criminal cases wherein the animal was implicated, and how in these cases human-animal relationships started to emerge.

From the vantage point of the courts, the animal was considered as a private property, and like any other property of high value, it was subsumed under the purview of the law. The animal’s owner was required to have the carabao registered, and every transaction involving the carabao was highly regulated by the colonial state. The height of the legitimization of the carabao was concurrent with the emergence of the agricultural economy dependent on exportable cash crops. As the global markets increased their demands for sugar, tobacco, abaca, coffee, and coconuts by the nineteenth to the early twentieth century, the significance of the Philippine carabao did not cease. In fact, the carabao was more wanted in the rural countryside.

At some point, the study of the carabao as a legal property became too transactional. Since the animal was treated as a property, the valuation of offenses rested on a plaintiff vs defendant model: between the owner and the criminal. The courts became the avenue to settle contestations involving the beast, and regardless of the result of these cases, the cases have shown that its owners fought until the very just for an animal.

But then again, this is not “just an animal.” As described above, the carabao possessed great economic value that spelled the difference between life and death for the farmer. It meant economic security and the fulfillment of debt obligations. It also meant the capability for the peasant to raise one’s household. The carabao was everything.

The study of carabaos as private property exhibits not only the valuation of the owner for the object owned, but the implicated relationships as well. The unique, intimate and enduring human-animal relationships are what compell the human owners to defend the non-human animals. The process of domesticating and taming the animal generates a relationship of mutual understanding between the master and the animal. Pet ownership is another frm of relationship wherein the animal is kept largely for entertainment purposes. The understanding of property, contrary to Marx, implicates relationships which are beyond economic measure.

Then perhaps in the study of carabaos one can get a glimpse as to why people fight for the things they owned (or believe to own). What is it that compells the Philippines in its fight for the Spratlys and the Paracel Islands? If the Philippines view these territories as their own, then what how does its people, who embody the sovereignty of the state, relate with their property? What pushes the Coast Guard to defend the domestic waters against fishermen of nearby territories? Can nationalism help define the entangled relationship of the owner and the object owned?

Relationships matter in identifying the root cause as to why we fight for the things that we own. But how far we are going to defend our relationships is another question altogether. Sometimes and I hope it does not get to this point, that in the most desperate of times and need and perceived hopelessness, extrajudicial solutions are deemed as tenable and justified in defense for the things that really matter to us.