Right before the year ended on 31 December 2019, cases of pneumonia of unknown origin and etiology were reported in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China. By 07 January, a novel coronavirus (CoVID-2019) was identified as the causative virus by Chinese authorities.

From Wuhan, the virus had spread quickly to other provinces. until it affected 24 countries including Japan, Korea, United States, Singapore, Thailand, Australia, France, Germany, the Philippines, United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam. As of 02 February, the World Health Organization reported that there were more than 14,600 confirmed cases globally, 98% of which were from China. Of this figure, more than 2,100 were considered as severe cases and had resulted in 304 deaths. Elsewhere, 1 death was confirmed in the Philippines.

Studies have consistently identified the source of the virus, namely, the Huanan seafood market. According to the latest The Lancet study, 49 (49%) of the 99 patients had direct exposure to the market where live animals were also on sale. This included (but not limited to) poultry, bats, marmots, and snakes — all found in one location.

Some writers have called for a ban on wildlife trade and consumption, citing historical linkages between animals and diseases, and sociological impact. While these are extremely important policies to consider in reducing the instances of animal disease transmission, it might also be prudent to also rethink the relationships that we have with animals as situated in their context.

Certainly, the coronavirus (CoV) affects the health of both animals and humans. Respiratory diseases and gastrointestinal conditions appear in domestic animals. For humans, the CoV mostly affected the upper respiratory tract and gastrointestinal tract, from mild self-limiting diseases such as the common cold to more severe forms such as bronchitis and pneumonia.

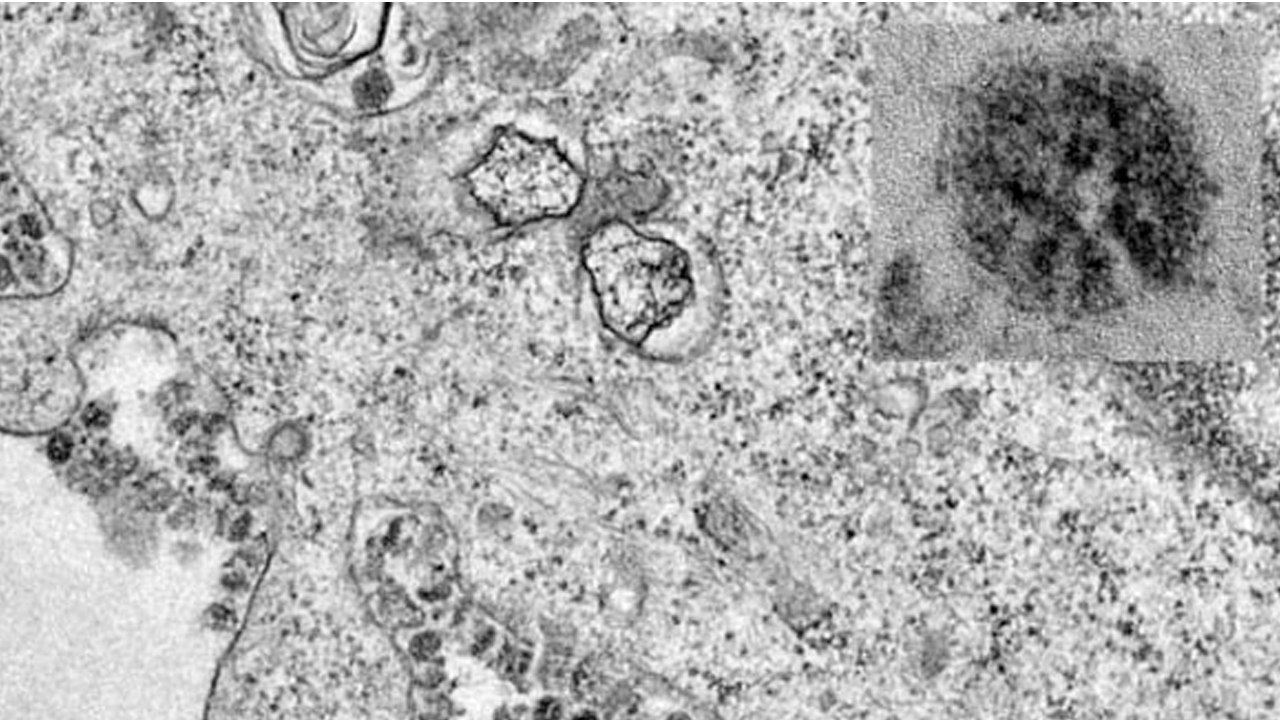

Source: The University of Hong Kong 2020

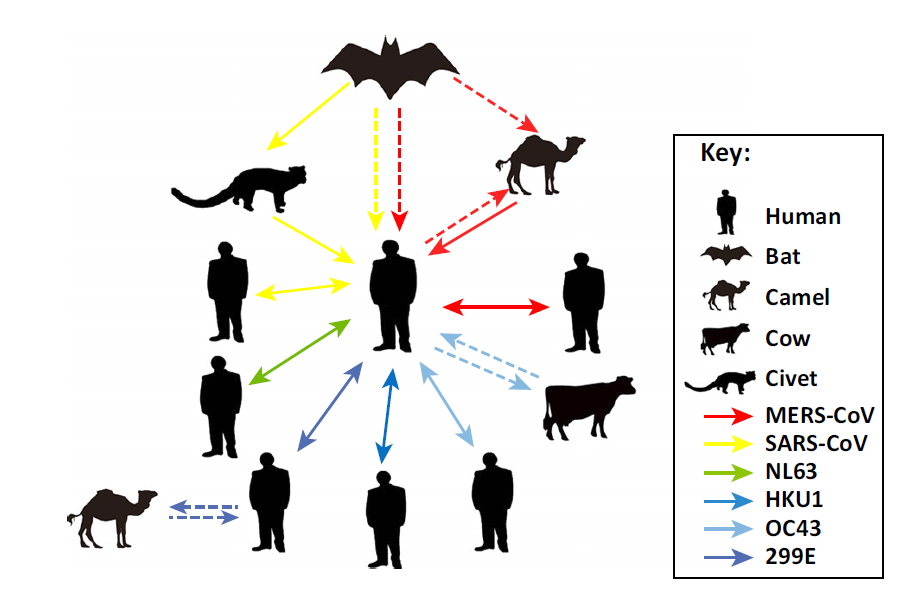

Since its discovery in the early 1970s, a variety of pathological conditions in domestic animals were attributed to CoV infections, such as canine respiratory coronavirus, bovine coronavirus, feline coronavirus, to name a few. The adaptability of CoVs differs in both animals and humans. Some of the CoVs are already adapted in humans (i.e., 229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1 Human Coronaviruses), causing mild diseases in humans with weak immune systems. However, in the case of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), these CoVs are not adapted in humans and are found mainly in animal reservoirs.

Source: Su et al. (June 2016). “Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses.” Trends in Microbiology 24(6), 490-502.

The transmission of disease from a vertebrate animal to a human is known as a zoonotic spillover. Spillover events are what concerns disease ecologists, scientists, and public health officials because these are highly undetectable. When it occurs, the zoonotic disease incubates into the new host for several days before it manifests and spreads to the new host’s population, with a wide range of lethal infections. More importantly, spillover events present a global public health burden the gravity of spillovers is aligned with ecological, epidemiological, and socio-cultural determinants.

Most of the fatal spillovers in recent history are brought about by constant exposure of wild animal reservoirs in spaces with dense human activity and/or domestic animals. The masked palm civets (Paguma larvata) were implicated as the route of the exposure of SARS-CoV in Guangdong Province in China in 2002. However, a closer examination of masked palm civets in the wild showed that they do not necessarily have the SARS-CoV. They only began to serve as intermediate hosts when they were placed in close proximity with other species, most especially the wild bats. These bats had detectable levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV. The recombination of the SARS-CoV was proposed through the evolutionary relationship between the two species which were found in the live animal markets in Guangdong Province, China, and sold off as exotic delicacies in restaurants.

But there were spillover events that occurred without the direct consumption of wild animals. In 1997, an influenza A(H5N1) infection was first detected in Hong Kong, receiving worldwide attention. Previously thought as an influenza virus that was confined only to avian species, influenza A(H1N1) was isolated for the first time from a human. It was first detected in May 1997, with no other cases reported for 6 months. Then, from November to December 1997, the second wave of infections occurred, with 17 additional cases resulting in six deaths. Epidemiological evidence suggested that fatal outbreaks of avian influenza occurred in the poultry farms in northwestern Hong Kong, with chicken coming into contact with geese pathogen from Guangdong Province in China. Most sources of live poultry also came from this province, which was postulated as the pathways of transmission. Sequencing suggested that direct chicken-to-human transmission of the virus occurred.

In both cases, animal geographies most especially farms, poultries, live animal markets, wet markets, and seafood markets are involved. Common throughout the East and Southeast Asian region, the concept of the ‘wet’ market as opposed to the ‘dry’ market served as a colonial measure that emphasized the boundaries between sanitary and unsanitary products. The conditions of these places contributed to the speed and risk of spillovers between animals and humans. Even without intending to consume wild animals, poor market conditions and animal handling allowed for greater exposure to unknown diseases.

Source: https://mustsharenews.com/wuhan-market-animals-menu/

In addition, the marketplace as a centerpoint for human and animal interaction is embedded in a network that connects the farm and wild areas to the household. It is also a space where those who are involved in the trade are competing against larger players. In a recent study by medical anthropologists, wet markets in China and across Asia are sites of struggle, where farmers, producers, and vendors face everyday pressure from large-scale industrial producers. According to them, “breeding wild animals can be a path towards a steady income when it remains a struggle to live off the land in rural China.”

The dissolution and ban of wildlife trade and consumption remove legitimate spaces for which rural farmers can participate in an industry that is heavily geared towards livestock farming. By removing such spaces, animal trade can be replaced with black markets sold from households or nondescript areas away from police surveillance and disease monitoring agencies. Thus, while wildlife ban may seem to be an easier solution, this move may pave way for a more difficult detection of zoonotic spillovers and animal diseases.

What is suggested is to look into the activities that allow for zoonotic spillovers to persist. A large portion of these spillovers is caused by human activity. The continued expansion of farmlands into wild areas, conversion of agricultural lands into a residential or industrial complex, and increased consumption of meat-based products are human transgressions to animal spaces. As more wild animals come into contact with domestic animals and humans, wild viruses and parasites that are not mapped out emerge and transgress human populations.

But it also entails understanding that the global solutions we are looking for are very context-specific. As we discover from the experience of this outbreak, Wuhan City is entangled in a complex network of global connections and local traditions. It has an international airport that connects its population of more than 11 million people. Community-level solutions may provide alternatives to wildlife trade, promote sanitary marketplaces, or educate food practices. As we try to research for new vaccines for the emerging infectious diseases, reevaluating our relationship with animals becomes a concomitant to public health.

Perhaps if we start seeing animals beyond as objects to be consumed, we may realize how closely intertwined they are into our health. Until we revisit our relationship with them, we should expect more zoonotic spillovers in the unforeseeable future.

This piece also first appeared in the Hong Kong Free Press.